50 Years Since Altair BASIC:

How Bill Gates’s First Major Program Launched Microsoft and Shaped the Digital Age

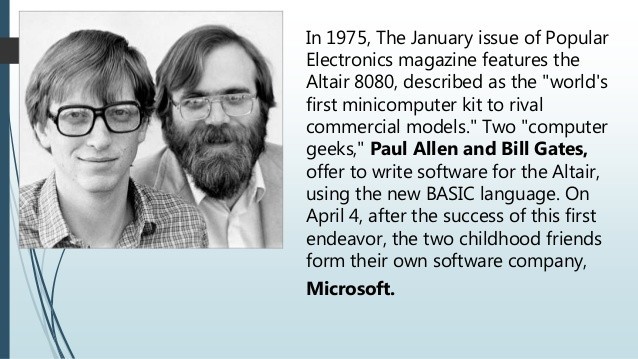

January 1975. A thin hobbyist magazine, Popular Electronics, lands on newsstands with a picture of a blue metal box and the words World’s First Minicomputer Kit. That box — the Altair 8800 — looked unremarkable to most readers. But to two young programmers in Seattle, Bill Gates and Paul Allen, the photo wasn’t just an image of a machine. It was a spark, a signal, an opportunity.

Neither of them owned an Altair. Neither had the money to buy one. But both had something just as powerful: years of self-taught programming, an obsession with computing, and the nerve to imagine that the future of software could start with a single program.

Within weeks, Gates and Allen were writing code that would become Altair BASIC, the first widely available high-level programming language for a microcomputer. That program didn’t just run on the Altair — it ran straight into history. It created the foundation for what would become Microsoft, transformed the economics of software, and cemented Bill Gates’s trajectory as one of the most influential technologists of the modern age.

This year marks roughly 50 years since Gates’s first major commercial programming success. To understand its significance, we need to rewind — back to teenage experiments in traffic data, back to the dawn of the microcomputer, and back to that fateful decision to code for a machine they had never touched.

Before Altair: The Lakeside School Years

Bill Gates’s fascination with computers began at Lakeside School in Seattle, where a group of students gained access to a time-sharing terminal connected to a General Electric mainframe. It was the late 1960s — a period when computing was still the domain of corporations, universities, and research labs. For teenagers, it was uncharted territory.

At Lakeside, Gates met Paul Allen, two years older but equally captivated by the puzzle of programming. Along with classmates like Paul Gilbert and Ric Weiland, they dove into every opportunity they could find: debugging code, writing small utilities, and negotiating extra computer time from companies who needed help finding errors in their systems.

The Lakeside environment gave Gates and Allen more than technical skill. It gave them confidence. They weren’t just learning to code; they were learning that code had real-world value.

Traf-O-Data: A Trial Run for the Future

By the early 1970s, Gates and Allen’s curiosity had grown into something more entrepreneurial. Together with Paul Gilbert, they launched a small venture called Traf-O-Data.

The premise was simple: use computers to process traffic flow data collected by roadside counters. In practice, it meant building an Intel 8008-based device, writing software to analyze tapes of traffic patterns, and producing reports for local governments.

Traf-O-Data was never a huge success. The hardware was clunky, the market limited. But the experience was invaluable. It taught Gates and Allen how to work with early microprocessors, how to translate raw data into useful results, and how to think about technology as a product.

Most importantly, it planted the idea that software — not just hardware — could be the centerpiece of a business.

The Spark: Popular Electronics, January 1975

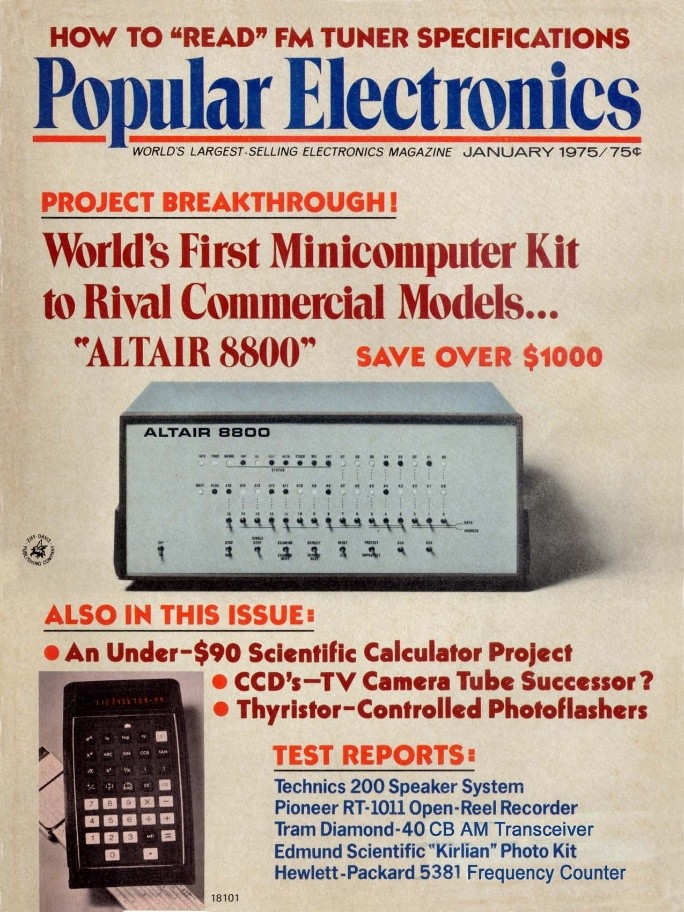

The real turning point came with the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics. The cover featured the Altair 8800, a kit computer developed by Ed Roberts of MITS (Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems). For hobbyists, the Altair was a dream: affordable, expandable, and available to order by mail. For Gates and Allen, it was a revolution waiting to happen.

They immediately saw a gap. The Altair was programmable — but only if you were willing to labor with toggle switches and machine code. What it lacked was a user-friendly language. What it needed was BASIC.

Writing BASIC Without an Altair

There was just one problem: Gates and Allen didn’t own an Altair.

Instead, they improvised. Using a PDP-10 minicomputer at Harvard, they wrote an emulator that could mimic the Altair’s 8080 microprocessor. On this virtual machine, they built their interpreter for BASIC (Beginner’s All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code).

Working around the clock, they optimized the code to fit into a mere 4K of memory — a task that required extraordinary ingenuity. They split tasks, debugged obsessively, and tested their work line by line.

Finally, in March 1975, Allen flew to Albuquerque to demonstrate the program to Ed Roberts. The stakes were high: if the code failed, the opportunity would vanish. But when Allen loaded the interpreter onto a real Altair, the machine came alive. It worked.

The Birth of Micro-Soft

That demo led to a licensing agreement with MITS. Gates and Allen’s interpreter became known as Altair BASIC, and thousands of hobbyists soon began programming the Altair with it.

In April 1975, Gates and Allen formalized their partnership, calling their company “Micro-Soft” (the hyphen was dropped a year later). It was, in essence, the first Microsoft product.

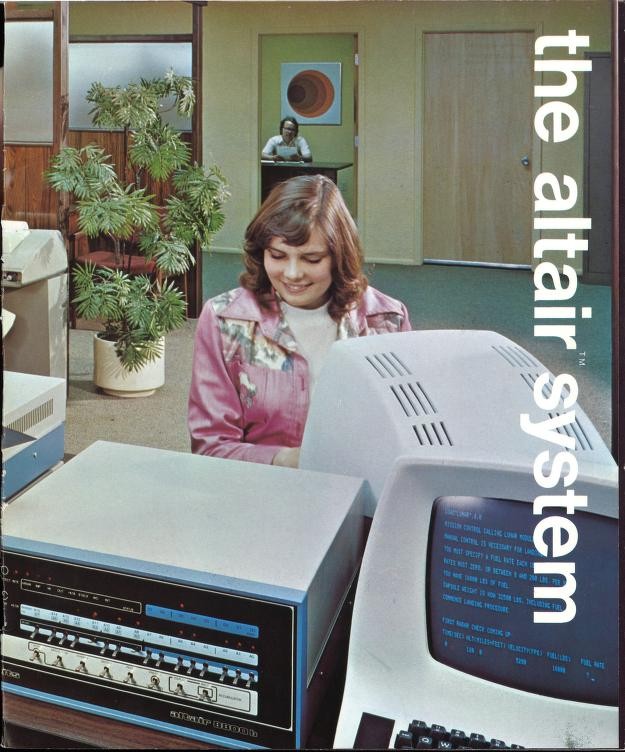

Altair BASIC was revolutionary not because it was flashy but because it democratized programming. Suddenly, ordinary users — not just engineers in labs — could write programs for their own personal computer.

Why Altair BASIC Mattered

- It proved the market for software. Before 1975, hardware was the main commodity. Software was often bundled or given away. Altair BASIC showed that software itself could be a product people would pay for.

- It seeded the culture of licensing. The agreement with MITS set a precedent for how Gates and Allen would later negotiate deals with IBM, Apple, and countless others.

- It validated Gates and Allen as serious players. They weren’t just teenagers tinkering anymore. They were entrepreneurs delivering a professional product that worked.

- It created a foundation for Microsoft’s growth. Every later triumph — MS-DOS, Windows, Office — can be traced back to the credibility and momentum of Altair BASIC.

The Myth, the Reality, and the Legacy

Over the years, the Altair BASIC story has acquired almost mythic status: two young programmers, a garage, a vision that outpaced the hardware of the day. Like many origin stories, the details can get romanticized.

Over the years, the Altair BASIC story has acquired almost mythic status: two young programmers, a garage, a vision that outpaced the hardware of the day. Like many origin stories, the details can get romanticized.

But the core truth remains: Gates and Allen’s first major program was a turning point not only for their careers but for the entire software industry. It was the moment when the idea of a software company became tangible.

Paul Allen later described the exhilaration of watching their code run on the Altair as one of the defining moments of his life. Gates has reflected that the experience shaped his belief that software could — and should — drive the future of computing.

Looking Back from 50 Years On

Half a century later, it’s easy to overlook the fragility of that moment. In 1975, the future wasn’t guaranteed. The Altair could have been a fad. The BASIC interpreter could have failed on demo day. Gates and Allen could have moved on to other pursuits.

Instead, their determination — and their code — turned a hobbyist kit into a platform for an industry.

Today, the notion that software is the soul of technology feels obvious. But in 1975, it was radical. Altair BASIC was the proof of concept.

Lessons for Innovators Today

- Start before you’re ready. Gates and Allen didn’t have an Altair; they built an emulator. They didn’t wait for perfect conditions.

- See the gap. They recognized that hardware without accessible software was incomplete. Innovation often lies in spotting what’s missing.

- Think scale. Altair BASIC wasn’t just for one machine; it was the seed of an idea that software could travel across platforms, markets, and decades.

- Build partnerships. Their collaboration — Gates’s relentless drive and Allen’s visionary instincts — was the catalyst. Innovation rarely happens alone.

Final Thoughts: From Altair to Everywhere

The story of Bill Gates’s first major program is not just a tale about code. It’s about foresight, risk, and the birth of a new economic model. Fifty years ago, a pair of young programmers bet on the idea that software mattered. They were right.

From the blinking lights of the Altair to the cloud-based ecosystems of today, the lineage is clear. The program they wrote in 1975 wasn’t just a tool; it was a blueprint for the digital age.

So, as we look back, the question isn’t just how far we’ve come. It’s also this: what new idea, written by some unknown programmer today, will define the next 50 years?

Sources & Further Reading

- Bill Gates, GatesNotes – “The Early Days of Microsoft” – reflections from Gates on founding Microsoft and writing Altair BASIC.

- Allen, Paul. Idea Man (2011) – memoir including firsthand accounts of Traf-O-Data, the Altair BASIC project, and the founding of Microsoft.

- Computer History Museum – “Altair BASIC and the Start of Microsoft” – archival material and timeline of events.

- Popular Electronics, January 1975 Issue – the magazine cover that introduced the Altair 8800 and inspired Gates and Allen.

- Microsoft Archives – History of Microsoft: 1975–1985 – official corporate history timeline.

- AP News – retrospective coverage on Microsoft’s 50th anniversary, including Gates’s reflections on Altair BASIC.

- Reid, T.R. The Chip: How Two Americans Invented the Microchip and Launched a Revolution – background on the era’s hardware and microprocessor culture.

- Isaacson, Walter. The Innovators (2014) – broader history of computing, with context on Gates, Allen, and early personal computing.

Further Viewing

- Bill Gates Reflects on Microsoft’s Early Days – GatesNotes video interview (Bill Gates on writing Altair BASIC and founding Microsoft).

- Paul Allen on the Birth of Microsoft – archived interviews where Allen recounts the Altair BASIC demo and partnership with Gates.

- Computer History Museum: The Rise of the Altair – lecture and panel discussions featuring early MITS engineers and hobbyists.

- Triumph of the Nerds (1996) – PBS documentary by Robert X. Cringely covering the Altair, Gates, and the software revolution.

- The Revolutionaries Series – Computer History Museum conversations with early Microsoft executives and contemporaries.

- The Mind of Bill Gates (2019) – Netflix docuseries Inside Bill’s Brain, which touches on Gates’s early fascination with computing.

Categories

Recent Posts

- Top 5 Super Bowl 2026 Ads — Why Viewers Loved Them & What Everyone Is Saying February 12, 2026

- Pantone Color of The Year 2026 – A Call to Calm December 9, 2025

- Crafting Emotion Through Light, Sound & Motion November 24, 2025

- Generative AI Isn’t a Shortcut — It’s a New Artistic Medium November 20, 2025

- Part 2: How Film Creates and Shapes Culture September 24, 2025

- Film as Mirror and Molder September 23, 2025

- 50 Years Since Altair BASIC: September 16, 2025

- Guides to the Past: The Story of Rockford’s Elks Lodge #64 September 15, 2025

- Generative AI: The Paint Tube of Our Era September 2, 2025

- From Script to Screen: Generative AI and the Transformation of Film Production August 19, 2025

Recent Comments